Towards a Confederative & Accountable Democracy

A Concept Paper Offered for Public Review and Discussion. © John J Coe 2019

Preface

This paper is an abridged version of the penultimate chapter in my work in progress, The Case for Christendom. It is offered here as a Concept Paper for public review and discussion. Your views and comment are invited and will be gratefully accepted.

Foundation Assumptions

1. That the liberal ideal of parliamentary representative democracy is facing an existential crisis across the face of the democratic world to the point that it is in dire need of review to render the ‘representatives’ of the people truly and accountably representative.

2. There is no point in attempting to reform the patient. To do so is simply window-dressing. Modern parliamentary democracy requires a root and branch shake out.

3. I confine my remarks to the system of parliamentary democracy, sometimes described as the Westminster style of government. The representative system of government in place in, for example, the United States of America is an idiosyncratic style of ‘republican democracy’ that is rightly deserving of a separate paper.

Who Should Rule?

This is perhaps the primary question in the political lexicon. First comprehensively addressed by Plato it has been the subject of countless debates and remains the tap root of political conflict. It has caused civil wars and brought peoples and nations to world wars. It is an insoluble question inasmuch the answers are as varied and legitimate as there are souls on the planet. Arriving at some broadly accepted consensus is the task of the philosopher, historian and political theorist.

No system of rule can ever be wholly acceptable or morally correct. All are predicated to time, place, circumstances and culture.

To further this discussion into some manner of C21st modernity, I put the simple proposition that any form of rule should be predicated to the principle that: the rule of all by one or by a few is tyranny.

This innocuous, seemingly self-evident sounding principle, itself raises apposite questions, chiefly: Is not the rule by all over the few, also a form of tyranny?[1]

So, who should rule to the satisfaction of all?

My model of government assumes that ‘citizens’ are freemen – members of a given group under governance. Indeed, the liberties, rights, obligations and security of this governance are not given to those who are not bound by deep allegiance to that group. Those that are thus bound may be designated as ‘Citizens’.

So, who rules:

An ‘Ideal’, being an Arché [2] [Includes theocracy]

The Demos – the people

A Group of Leading Citizens

The King

The Wisest

The Most Experienced

The Strongest

The One with the Most Popular Support

The One Ordained [Medieval]

The Noblest [Ethics]

The One with all of the Above

All of the foregoing, despite their individual limitations, indicate qualities required in government. It is highly unlikely that these qualities will be embodied in a single person or even a small few. So, what to do?

Let us therefore examine in more detail the nature of the qualities required for effective, open and non-tyrannical rule.

Virtues / Qualities in Government

Wisdom

Justice

Virtue

Ability

Strength

Compassion

Experience

Nobleness

Honour

Reflective [Representative]

Entrepreneurial

Nota Bene. I commend all these ‘Qualities’ as being the moral fundament of government.

Representative Democracy?

If voting made any difference, they wouldn’t let us do it.

[Attributed to Mark Twain]

Reflecting upon the mess that is contemporary political life, I address two obvious and interrelated questions: Where does authority lie? What is the legitimacy of political authority in our political system?

Until recently I held, quite naively, that such authority resided in the people. I held that the individual citizen was the source of political authority – he or she knew their individual interests best – and, acting in concert with their fellows, they had, through the election process, the regular opportunity to choose a representative to best articulate those interests in a national assembly of representatives. This system is broadly described as liberal representative democracy.

Of late however, disenchanted with this ideal, I have been drawn into some dark political corners. I have come to the realization that, generally speaking, the ‘people’ - the citizenry – despite being the fundament of liberal democracy, care not one iota about the detail of their government. By this, I do not describe the everyday ‘whining’ and complaining about politicians and the state of the world in general – such empty noise does not cut the mustard. In my terms ‘care about’ implies the actual and practical engagement of the people with the political process: specifically, the direct holding to account of their political representatives. Experience has amply shown us that unless we are willing, or compelled, to shake our politicians by their coat-tails they will do nothing – worse still, they will let anything happen.

Civic duty requires the citizen to engage with the political process. Sadly however, experience has also taught us that relying on the ballot box is an insufficient civic duty in itself.

I have come to accept the reality that the much-vaunted ballot box of liberal democracy is in reality a mere chimera, a bromide to maintain the illusion of participation in the political process. Realistically, how often does the citizen in a liberal democracy get to exercise his democratic right through the ballot box – ‘once’ in every term of office – which in some countries such as the United Kingdom means once every five years!

How liberal, how democratic and how representative is that?

Between the irritating interruptions called ‘elections’ the politician is able to run riot, do nothing, accept the perquisites of office and live off the taxpayer whilst treating his electors with complete-ignore. For several weeks before polling day the politician sleazes back with a sack-load of promises in an endeavour to buy his way back into office. Then and only then are the electors able to decide upon his fitness to remain as their representative. In the ‘muddle’ of nonsense that is electioneering, much of the failings of the individual politician in question is overlooked in the hype of the moment and, lo and behold, the ‘same-old-same-old’ is voted back into office.

Pro-tem the nation slides inexorably into directions no one wants because of his neglect, because of his deals made with the Devil, and even worse, because of his active acquiescence of policies introduced without either the knowledge or support of his constituents.

And they call this Democracy!

Liberalism in Political Disarray

Although the roots of political and social ‘liberalism’ lie in the writings of, Thomas Hobbes, Adam Smith, John Locke, Baron Montesquieu et.al. ‘liberalism’ as we know it today was, in my view, introduced to us in the C19th through, variously: John Stuart Mill; the actuality of the free trade debate in Britain and the evolution of the Liberal Party. I contend that the notion of Westminster democracy reached its political articulation in Walter Bagehot’s classic work The English Constitution [1867] and, perhaps, reached its apogee in the societal reforms in William Gladstone’s four ministries.[3]

Since then, the term ‘liberal’ has been borrowed by countless political journeymen to justify their cause to the point it has become meaningless.

To return to its roots, I understand ‘Liberalism’ as being based on certain assumptions about man, the citizen and the individual. Looking back in context, these founding assumptions were based on religious and civic virtues much different to ours today.

I suggest that, to work effectively, liberalism must be based on agreed notions of wrongness and rightness; of mutual respect; a strong and agreed civic culture; an agreed sense of manners, consideration and so forth – notions that are in sad repair today.

Indeed, reasons for political disenchantment are manifold. However, cut to the bone:

Liberal democracy is a political ideal that was the product of, and was suited to, a different social milieu – a less complex social milieu that valued to a far higher degree, the notions of integrity, trust, honesty, fidelity, faith, civility, obligation and responsibility.

It laments for an age past:

When politics meant more than a well-paid career

When politicians were concerned more about their constituents and their country than the next election and their pensions

Wherein ordinary citizens felt as though they had some direct influence over their political representatives

When politicians came from, and realistically reflected, the views of the constituents they purported to represent

Before big power party politics

Before factional deal making

Before electronic media and celebrity culture

Of better educated electors

When reasoned argument; considered and sound policies; fiscal responsibility; political integrity and mature leadership were significant factors in the electoral mix

Of genuine free speech, wherein people felt free and were allowed to say their piece

When politicians actually addressed the people without a carefully scripted media parade

When politicians actually listened to their electors

When not only did politicians listen to, but acted upon, the wishes of their constituents

When representative democracy meant just that

The reasons for the systemic decline of liberal democracy have been detailed in manifold quantity and in varying quality elsewhere: these include:

The rise of a political class and political elites

The failings of the so-called ‘Fourth Estate’[4]

The existence of a politically driven ‘progressive’ elite committed to social engineering and total societal transformation

The rapidity of technological change

The decline of spiritual faith

The decline in civic faith

The decline in responsible parenting

Declining educational standards

The rise of modern nihilism

The primacy of the ‘Me’ culture

The rise of the ‘popular moron’ and the celebrity culture

The increase in societal greed and material expectations

The contemporary self-fulfilling expectation of corruption that holds that because everyone’s ‘on the fiddle’ so why not politicians?

And, of course, the final and absolute negative – the fact that most people just don’t care enough to do anything about it – Period.

A Confederative & Accountable Democracy – Political Structure

How then can we design an effective, representative and accountable government that takes into account the mix of merit, popular election, institutional appointment, tradition and cultural nuance?

In developing my idea of a Confederative & Accountable Democracy I retain what I consider to be the best of the liberal ‘idea’ of government.

Foremost among these is the idea of an accepted written or unwritten[5] Constitution to serve as the fundament of the nation and its political identity. To this are addended a written Bill of Rights and its corollary, my own National Covenant of Obligation.[6]

These three protocols should enshrine the traditional liberal notion of the separation [balance] of powers between the Executive, Legislative and Judicial arms of government. The documents should enshrine the citizen’s individual political rights and, significantly, detail the citizen’s obligation to his country.

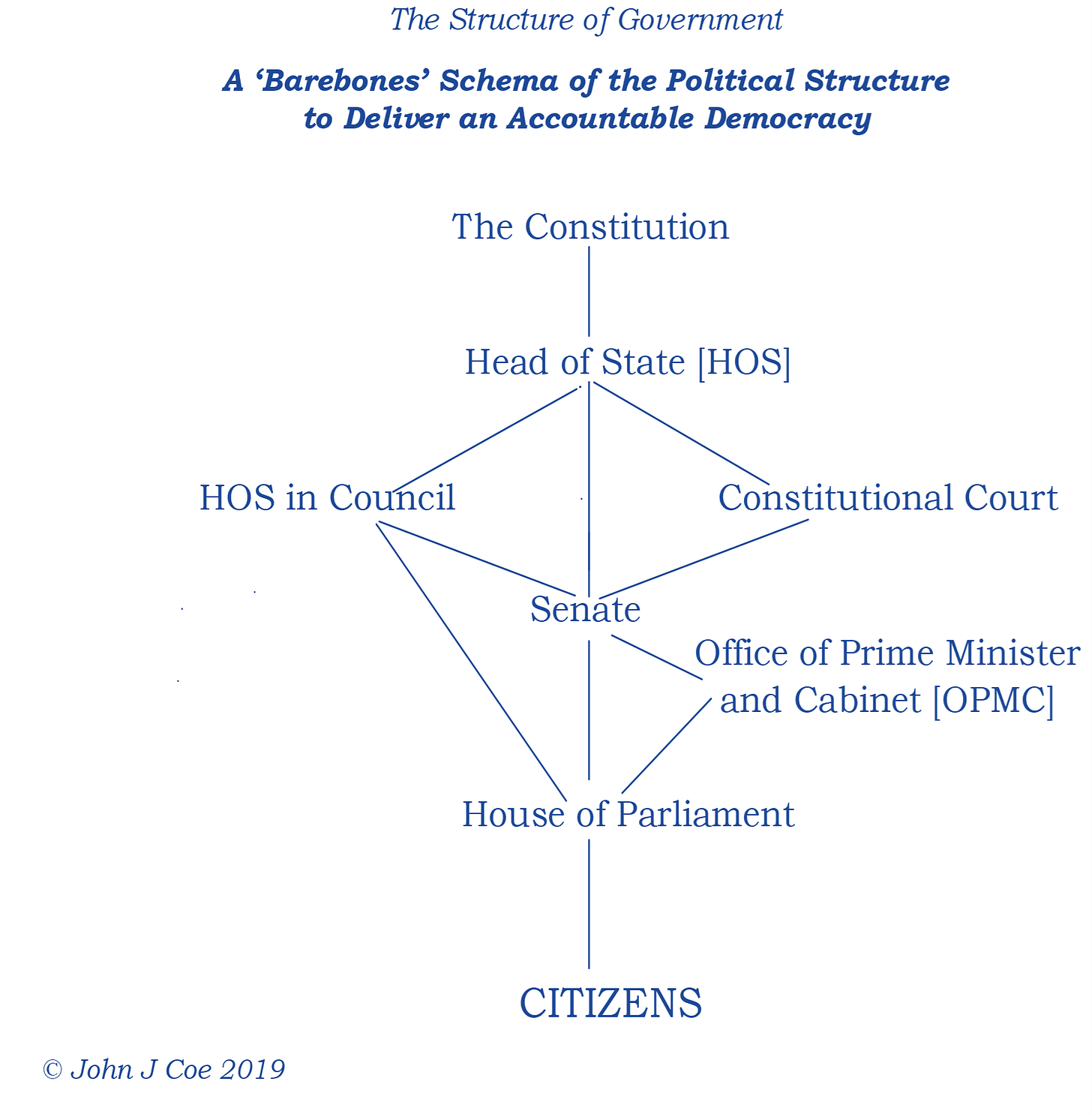

In brief, I posit a three-tier structure of government:

I. Head of State [HOS] being the Senior Executive

II. A Bicameral Parliament comprising: a Senate and a House of Parliament

III. Constitutional Court

On face-value the foregoing is not much different to any operating democratic political system of the present day. I suggest however considerable structural and accounting changes.

The Head of State, unless extant because of cultural tradition e.g. a hereditary monarchy, is chosen by the citizens by popular [universal] petition from the ranks of the military, the police, the judiciary or from academia. This choice must be supported by seventy percent [70%] of a joint sitting of both houses of the parliament.

The Parliament is a bicameral legislature:

The Senate comprises a determined number of ‘confederations’, encompassing the totality of the nation’s socio-economic life, together with professional and specialist confederations. Each confederation freely elects from within its members a determined number of delegates to the Senate to represent the interests and views of their confederation.[7]

The House of Parliament is the Citizens’ House. It comprises representatives elected by the citizens directly in traditional geographical electorates through a non-compulsory universal franchise.

The Constitutional Court is the judicial arm of government. It comprises five [5] senior jurists recommended by a Select Committee of the House of Parliament; supported by a seventy per-cent approval [70%] of a joint sitting of the Senate and the House of Parliament and ratified and appointed by the HOS. The Constitutional Court is concerned only with cases appertaining to the matters of government and the constitution.

Moving away from standard representative government structures, I also formally include two further adjunct offices of government in my proposed political structure. These are critical to the idea of effective and accountable government:

The Office of Prime Minister and Cabinet [OPMC] is also part of the executive arm of the Government. It should comprise those representatives able to attract and maintain sufficient votes [support] from the floor of the House of Parliament to be thus deemed to enjoy the confidence of the House. These will be charged with assuming government by the Head of State.

The Head of State in Council [HOSC] operates under the direction of the office of the HOS, assisted by Constitutional Court judges and the Executive Officers of the Senate. It is responsible for providing oversight of the effective audit and assessment of the government.

Explication

My proposal explicitly accepts Baron Montesquieu’s [1689-1755] theory of the separation of powers as detailed in his The Spirit of the Laws [1748]. In essence he argued that by keeping the three arms of government separate and in balance, the possibility of one of them, particularly that of the executive, accruing too much power to the severe disadvantage of the citizens, would be reduced, if not completely avoided.

This idea of power separation forms the foundation of liberal democratic governance. In some instances, it has resulted in political gridlock or, particularly in those democracies with a fusion rather than a distinct separation of powers, it has seen power creep, usually to the prime minister’s office or to the judiciary.[8]

It is however, also my intention that not only should these powers be separate, but that they will be compelled to address the concerns, and enhance the aspirations of the citizens, by my inclusion into the political structure of specific mechanisms of internal interrogation and audit.

****

My proposal draws freely from both syndicalist political theory of the C19th and the C20th notion of political corporatism.

Syndicalism was a revolutionary socialist doctrine that advocated the workers taking power by seizing the factories in which they worked. Developed in the late C19th it found its greatest support in France, Italy and Spain. Syndicalists envisaged the state being replaced by worker-controlled units of production. By 1914 the movement had lost its political momentum.

The formal idea of the ‘corporate state’ may be attributed to Benito Mussolini [1883-1945] who, between 1925-29, synthesised various ideas of model socialism and syndicalism to develop his theory of corporatism.

This theory replaces the traditional idea of parliamentary representation based on geographical electorates and universal suffrage, with corporate representation.

In my, highly democratised, Confederative view of such a state, the Senate comprises a determined number of corporations, to be known as ‘Confederations’. These, together with specific professional and specialist confederations, will encompass the totality of the nation’s socio-economic life.

It should be noted and emphasised that it is not intended that these confederations should serve as ‘special interest’ or ‘lobby’ groups representing minority interests with the ability to hijack the implementation of effective government policy for all. It is also imperative to note the dangerous contemporary inversion of de Tocqueville’s concerns of the ‘tyranny of the majority over the few’: Some contemporary political systems have endeavoured to be so democratic and inclusive with the result that their entire political processes have, on occasion, been gridlocked by spurious minor ginger groups elected on a totally unsustainable and unaccountable proportional representative basis.[9]

It is intended therefore that the citizen is obliged to join a minimum of one and maximum of three bona fides and nationally constituted confederations suitable to his employment, recreation and domiciliary/social circumstances. As detailed above, each confederation freely elects from within its members a determined number of delegates to the Senate to represent the interests and views of the confederation.

Thereby is the individual citizen, in addition to his right to elect a representative to the House of Parliament, provided with a further indirect voice in government affairs. The rights and interests of all citizens are, therefore, further indirectly enhanced and rendered transparent.

****

Following directly on from this confederative Senate structure is a further novel feature of my proposal, being the idea of Senate Adjunct Policy. In essence, this is a process of national policy aggregation and preparation effected by individual confederations in the Senate.

Traditionally government policy owes its fundament in competing electoral platforms in the electoral market place. This crude vote buying exercise is, as often as not, debased by blatant ‘pork-barrelling’ popular appeal rather than considered analysis and carefully-crafted legislative proposals. Serving to further debase the political mix are the various political considerations centred around ideological agendas or effective interest group lobbyists resulting in increasingly mediocre governments focussed on electoral cycles and power for the sake of power.

The concept of Senate Adjunct Policy suggests the preparation of government policy based on the aggregate of the wishes and aspirations of the citizenry seen through the eyes of their particular confederation. This aggregate is generated by computer software by which each citizen is connected to his or her confederation through his/her own encoded personal digital devices thereby enabling the registration of his/her concerns as and when requested.

This aggregated data would accurately reflect the current and prioritised concerns and aspirations of the citizens across the country by regions and sub-regions; reflecting the full gamut of the citizen’s public and private life. This data would then be refined into concise and practical working assessments of confederation views. These assessments are then put to the open Senate for consideration and formulated into effective Senate policy.

The successful results of the policy formulation and review process are termed Senate Adjunct Policy. This Adjunct Policy is passed down to the House of Parliament for information and comment before being passed to the OPMC for incorporation in its own policies based on its electoral platform.

****

The central feature of my proposed model of democratic accountability is holding the government of the day to direct account.

It will be noted that both the HOS and OPMC are designated in my model as being the Executive arm of government. Both have, however, a clearly delineated and separate focus in the Constitution. The Head of State has oversight of the function and legitimacy of government. The OPMC has the effective executive carriage of policy and legislation and a duty to implement the effective administration of government.

A recurring problem with existing variations of the OPMC around the democratic world is that there is no sound and regular authority to rein in the excess, the red herrings and the political agendas extraneous to the stated promises and policies made and contained in the electoral platform. Thus, all too often, a political party is elected to government on a particular policy platform with a mandate to achieve such and such, only, once it attains government, it chooses to disregard its promises and moves in tangents for which it has no mandate.

Under the terms of my model, the OPMC remains, of course, responsible to the citizens through the House of Parliament. However, a critical addition to the accounting process is that it will also be responsible to the citizens by a regular audit process of the government’s Key Performance Indicators [KPIs].

I suggest therefore, that the political grouping [party] charged with assuming government must, at the outset of their term of office, provide clearly enunciated KPIs to the House of Parliament, to the Senate, to the Constitutional Court and to the Head of State. Every twelve months the OPMC will be subject to a detailed audit and assessment process of these KPIs undertaken under the direction of the office of the Head of State, assisted by Constitutional Court Judges and the Executive of the Senate. This body constituting the Head of State in Council [HOSC].

These audit processes should be specifically centred on the effective implementation of stated and accepted policy, and to detect government diversions down paths beyond its remit and mandate. This process will provide the government the opportunity to explain problems, shortfalls and failures in its administration and the passage of policy. Should a government be found wanting it may be directly instructed to redirect and readdress the matters in question or, in extreme cases, the OPMC may be dissolved to begin de novo.

Description

The following details describe the nature and structure of the proposed government of a Confederative & Accountable Democracy.

The Head of State [HOS]

Description: The senior executive arm of government.

Composition: May be determined by cultural tradition as appropriate e.g. a hereditary monarchy, or chosen by the citizens by popular [universal] petition from the ranks of the military, the police, the judiciary or from academia. This choice must be supported by seventy percent [70%] of a joint sitting of both houses of the parliament.

Function/Duties:

To provide legitimacy to national government

To serve as the formal Head-of-State

To serve as Commander-in-Chief of Defence Force

To convene and dissolve government

To review, reject and authorise legislation

To provide sound oversight of government audit and review processes

To provide national ceremonial focus

To accept popular petitions[10]

Responsible: To the Citizens through the Parliament.

The Parliament

Description: A Bicameral[11] Assembly, being:

1. Senate

Description: A constitutionally appointed House of Audit & Review & Specific Policy Aggregation.

Composition: A confederative national assembly [and variation of the ‘syndicalist’ model[12]] comprised of elected delegates from cross-sectional national groups to reflect industry, commercial, community interest, religious, defence, security, and strategic planning confederations. The following is a suggested example only of such confederations:

Confederation of Business & Commerce

Confederation of Transport & Industry

Confederation of Agriculture

Confederation of Science and Technology

Confederation of Unions

Confederation of Mining and Resources

Confederation of Energy and Infrastructure

Confederation of Medicine and Hospitals

Confederation of Health and Welfare

Confederation of Education

Confederation of Local Government

Confederation of Arts & Recreation

Confederation of Community Interest [groups]

Religious Leaders

Vice-Chancellors of leading universities

Senior Civil Service Departmental Heads

Defence and Security

Functions & Duties:

To elect a Senate President and a six member Senate Executive.

Policy Aggregation. Through appropriate technology, aggregate data reflecting the accurate, current and prioritised wishes and aspirations of the members of each confederation across the country by regions and sub-regions. From this data formulate Senate Adjunct Policy.

To consider broader national economic and security issues.

To consider long-term across the board national planning issues.

To produce Senate Adjunct Policy based on these considerations.

Deliver this Senate Adjunct Policy to House of Parliament for information and comment for the Office of Prime Minister and Cabinet [OPMC] for incorporation into formal government policy for implementation.

Establish appropriate Key Performance Indicators [KPIs] by which to evaluate the implementation of this policy and to establish KPIs to assess general government performance.

To provide oversight of the smooth running of the House of Parliament and the administration of the OPMC.

Responsible: To the Head of State

2. House of Parliament

Description: The Citizens’ House.

Composition: Elected directly by citizens in traditional geographical electorates through a non-compulsory universal franchise.

Functions & Duties:

To elect the Speaker of Parliament together with a six-member Parliamentary Executive.

To elect the Prime Minister and Cabinet. To provide a prime minister and a group of supporting cabinet ministers whose election policies and promises found the greatest favour at the national election.

To provide oversight of the effective implementation of these policies and promises together with the Senate Adjunct Policies, thereby facilitating the sound administration and security of the country.

To provide effective oversight of the OPMC in the execution of its duties through committees and parliamentary debate.

To provide an open forum for the citizens’ representatives to raise and debate any and all issues raised by or concerning their electors.

To provide effective channels and measures by which these issues may be addressed.

To receive and address citizen petitions directed to and annotated by the HOS.

Individual Representatives to prepare Annual Reports detailing their activities, expenditure and contribution to the Parliament to be subject to annual review by the Parliamentary Executive.

Responsible: To the citizens.

The Constitutional Court

Description: The Judicial Arm of Government.

Composition: Constitutional Court Judges. Five [5] senior jurists nominated by the OPMC and appointed consequent to seventy per-cent approval [70%] of a joint sitting of the Senate and the House of Parliament, subject to ratification by HOS.

Functions & Duties:

To consider matters pertaining to the Constitution and matters directly pertaining to the execution of government.

To consider matters pertaining to defence and the security of the state.

To consider any declaration of and/or involvement in, War.

Responsible: To the Head of State

Office of Prime Minister and Cabinet [OPMC]

Description: The Sub-Executive Arm of Government.

Composition: Those representatives able to attract and maintain sufficient votes [support] from the floor of the House of Parliament thus deemed to enjoy the confidence of the House. These will be charged with assuming government by the Head of State.

Functions & Duties:

The preparation and presentation of proposed government policy to include Senate Adjunct Policy.

The day-to-day implementation of government policy

The administration of national government for the well-being and security of the nation.

Subject to annual KPI audits by the Senate.

Responsible: To the citizens, to the House of Parliament, the Senate and the Head of State. The OPMC will be immediately and directly responsible to the House of Parliament during periods of audit and review.

The Head of State in Council [HOSC]

Description: The HOSC is the Audit Arm of government under the direction of the HOS.

Composition: The HOS, Constitutional Court Judges and the Executive of the Senate.

Functions & Duties:

Conduct Annual Audits of the OPMC as to its policy implementation and general performance in government against the PKIs submitted by the OPMC and developed by the Senate.

Responsible: To the Citizens through the House of Parliament.

Summation

I commenced this paper by observing that I was going to address two obvious questions: Where does authority lie? What is the legitimacy of political authority in our political system?

I consider that I have done this. I have confirmed my belief that authority does indeed lie with the citizen. However, I have suggested that currently, for demonstrated reasons, this authority exists in practice only once over the electoral cycle.

My model of Confederative & Accountable Democracy works twofold. Founded upon the assumption that the citizen is the foundation of authority, and the source of legitimacy for the exercise of that authority, my model not only compels the representatives to account, it provides the citizen with greater opportunity to participate in the political process.

****

If the aim of democratic governance is to provide stable political outcomes that reflect the aspirations, concerns and desires of the electors, I humbly propose that my model of government will amply deliver these.

I have entitled this model Confederative & Accountable Democracy because it is precisely that – it is confederate and it provides accountable governance to the electors.

This model:

Retains the principles and many of the traditions of classic liberalism

It provides both direct and indirect input by the citizens into the political and legislative mix

It ensures this input is heard and addressed

It enshrines the principle of checks and balances by the unambiguous separation of power

It holds the government of the day directly to account by a regular audit process

It provides political transparency for the citizens by ensuring that their political representatives are subject to annual audit

It ensures that the elected government is compelled to act on its promises or be answerable to the full force of the law

****

The voice of the people permeates this model.

Foremostly, the franchise extends only to citizens of the country. Those with dual nationality, permanent residents, incarcerated prisoners, the insane, newly-arrived immigrants and those under eighteen years are excluded.

By their obligation to join a maximum of three only confederations, and through their participation in the public affairs of their confederation, citizens are rewarded with indirect representation in the Senate. This compliments their right to participate in the public political process and their right to the direct election of their representatives to the House of Parliament.

Moreover, through the notion of ‘petitions’, citizens have a further right to raise their concerns directly with the Head of State, who in turn is obliged to consider same and make comment before sending it down to the House of Parliament for consideration.

As ever, there is nothing prohibiting the citizen from joining a political movement or party. Thus is the citizen demonstrably linked to the political process.

Through the confederate nature of the Senate, the totality of commercial, industry, regional, societal and community groups are provided, equally, with direct input into the political system. The dynamic between confederations removes from the upper chamber of government the scourge of party politics. Moreover, this will also obviate the existence of that egregious excretion on our political system, the lobbyist. Indeed, the Senate will provide for a totally fresh form of representation, providing the opportunity for the citizen’s workplace, his education, health and welfare to have some direct say in shaping government policy. This structure aims to provide a new and total-democratic dimension to the idea of political representation.

I believe my model describes a secular, constitutional and accountable democracy. I commend it for your consideration.

ENDS

[1] See Alexis de Tocqueville [1805-1859]. French historian who, after his examination of the governance of the United States, suggested the idea of the tyranny of the majority.

[2] Arché. Origin; principle; first cause; from which emanates. [Aristotle].

[3] Trevelyan G.M. History of England. Longmans. London. 1966. See Book Six Chapter IV ‘The New Reform Era’. pp. 679-694.

[4] The press, media

[5] Unwritten Constitution: a constitution not embodied in a single document but founded on custom and precedent as expressed in statutes and judicial decisions. The UK is a good example of a polity with an unwritten constitution.

[6] Previously published on my former website www.mordechaibrown.net

[7] Confederation: A union or alliance of like-interests.

[8] Fusion of Power. A pollical system based on parliamentary executive, such as the United Kingdom, creates a fusion of the legislative and executive functions of government.

[9] Examples of this democratic electoral overreach include Israel, Australia and New Zealand.

[10] Petitions: Quite obviously within certain moderate guidelines.

[11] Bicameral. A legislative body having two chambers.

[12] Syndicalism. C19th political ideal proposing units of workers, social interest groups and so forth.